Pharmacists on the front lines

SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital pharmacists fill important role in patient care

When Nick Anglim started at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital during his second year of pharmacy school in 2007, the pharmacy department looked a little different.

“When I first started, we did not have pharmacists out on the floors rounding with teams. We did not have a pharmacist in the intensive care units.. We did not have pharmacists working with our cancer and blood disorder patients in our outpatient chemotherapy clinic or the inpatient cancer ward,” he said.

That’s all changed in the years since. In 2015, Cardinal Glennon hired a clinical coordinator to start a clinical pharmacy residency program, and the department began to expand its clinical services. Pharmacists now work alongside the rest of the medical care team in general medicine, infectious disease, cardiology, pulmonology, infusions and many more areas.

“I’m lucky enough to have been here from the beginning and see part of that, and expand my own knowledge, expand my own experience, and get to do it all in a place that I really, really enjoy working,” Nick said.

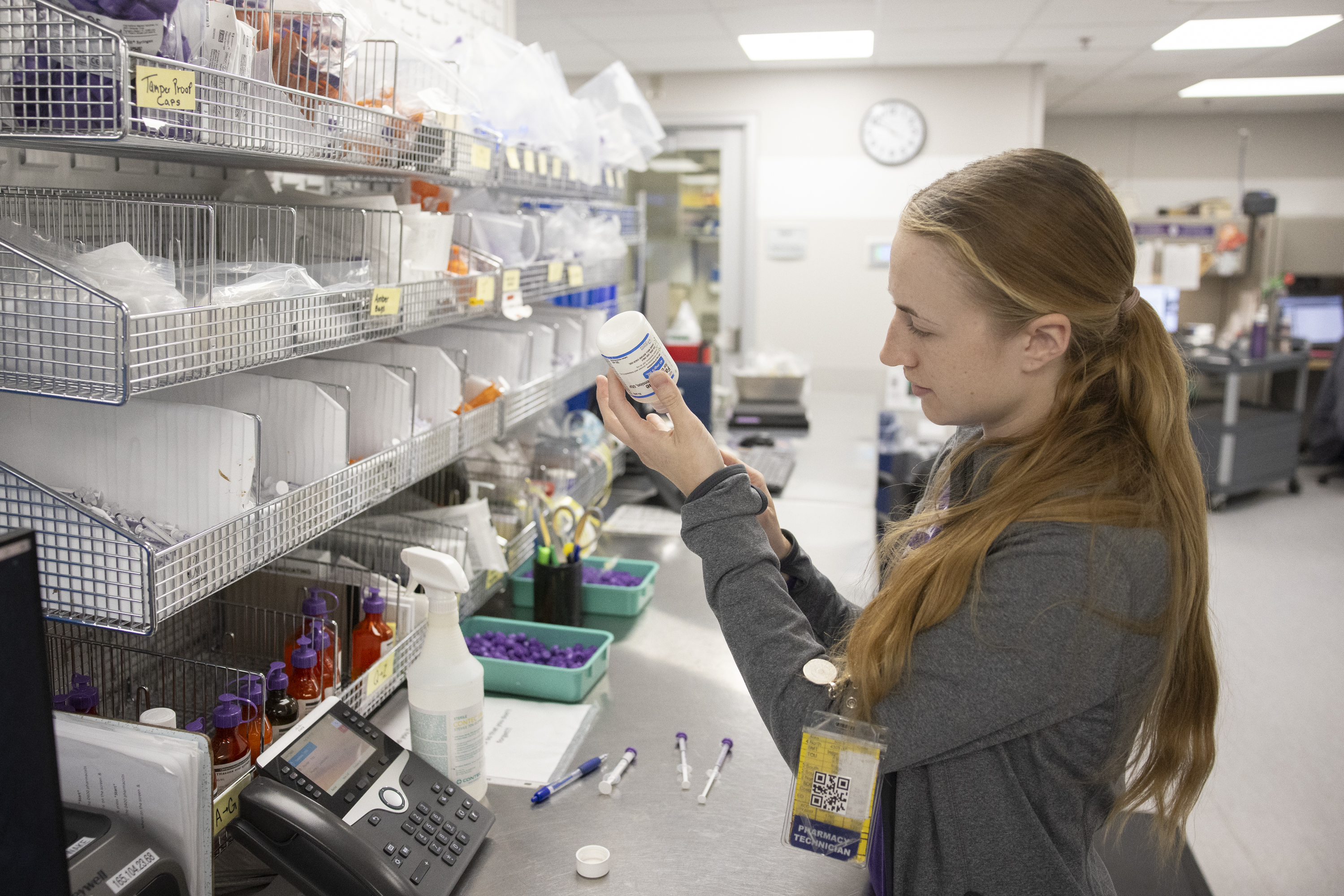

Cardinal Glennon has both an inpatient pharmacy and outpatient pharmacy. The inpatient pharmacy includes the clinical pharmacists who work with patients staying at the hospital, while the outpatient pharmacy serves as a community pharmacy to dispense medications for those not staying at the hospital.

During patient rounds, pharmacists work together with the rest of the medical team to figure out appropriate care. If a patient came through the ER with pneumonia, a UTI or an ear infection, for example, Nick might suggest a different antibiotic or dose based on the type of infection the doctor diagnoses.

“We do take care of medically complex patients who have seizure medicines, medicines for cerebral palsy, medicines for everything under the sun,” he said. “We do a lot of medical histories with families, making sure they are taking everything as prescribed and reported, and then adjusting their home medication list.”

They also help patients get ready for discharge, “training and educating families on new medicines, making sure they actually have access to those medications,” he said.

Brooke Judge, another clinical pharmacist, was interested in pediatric pharmacy from her earliest days in pharmacy school. She also gained experience in an adult hospital, the Missouri Poison Center, Cardinal Glennon’s outpatient pharmacy and the Cardinal Glennon emergency department before entering her current role as a clinical pharmacist in general medicine.

Working in a children’s hospital provides interesting challenges, Brooke said. “I’m working with kids of all different ages, right? So my NICU baby is different from my 15-year-old in the way they can absorb certain drugs and what they can and can’t have, what’s approved, do they have the right enzymes to help break down drugs or things like that,” she said. “So instead of just knowing essentially one developmental stage (like adults), I have to know multiple developmental stages and how that plays into the role of pharmacy. That’s what is intriguing to me. It keeps me on my toes.”

Since many children cannot swallow pills, pediatric pharmacy also involves more compounding of liquid medicines, which are prepared by the pharmacists. Many more established guidelines exist for adult medicine, so figuring out the best care for pediatric cases often involves more research into primary literature, Brooke said.

“We’re like detectives a lot of times, and problem solvers,” she said. “How do we make this work for the patient, and what’s best for the patient, what’s safest for the patient?”

Cardinal Glennon is a teaching hospital, and the pharmacy department recently welcomed its 10th residency class of four students, up from three last year and two originally. Pharmacy students also do rotations for about five weeks at a time.

Some people say they can’t imagine working with sick children all day, Nick said, but to him, it’s been incredibly rewarding.

“It’s not about seeing the sick kid,” he said. “It’s about seeing the kid and helping them to get better.”

The team was preparing for a child’s kidney transplant later that day — which means a child was about to have his life “drastically changed and improved,” Nick said. “It’s a lot of medical complexity that goes along with it, a lot of medications; it switches from dialysis to transplant medications to help prevent rejection and things like that, and not needing to take all these medicines for end-stage kidney disease. (It’s) having a healthier kidney and growing and going to school and all these things. We’re able to be part of that transition and watch these kids turn the corner.”

Brooke’s favorite days are when she gets to participate in celebration walks for kids who are leaving the hospital after extended stays. “I can’t even put it into words how that makes me feel to be part of that, knowing that I helped that child continue into being probably something great,” she said.