United against violence

Catholic students, schools add voices to national conversation

School shootings have prompted debates about gun control and conversations about mental health, but the recent shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., has added another voice to the discussion: the high school students themselves.

On March 14, teenagers across the country participated in the National School Walkout to honor the 17 students killed in Florida and to call for gun policy changes and an end to violence. Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School, Trinity Catholic High School, and Christian Brothers College High School were among participating schools in the St. Louis area.

They and other Catholic schools added prayer to needed conversations about gun control and mental health.

Prayer service

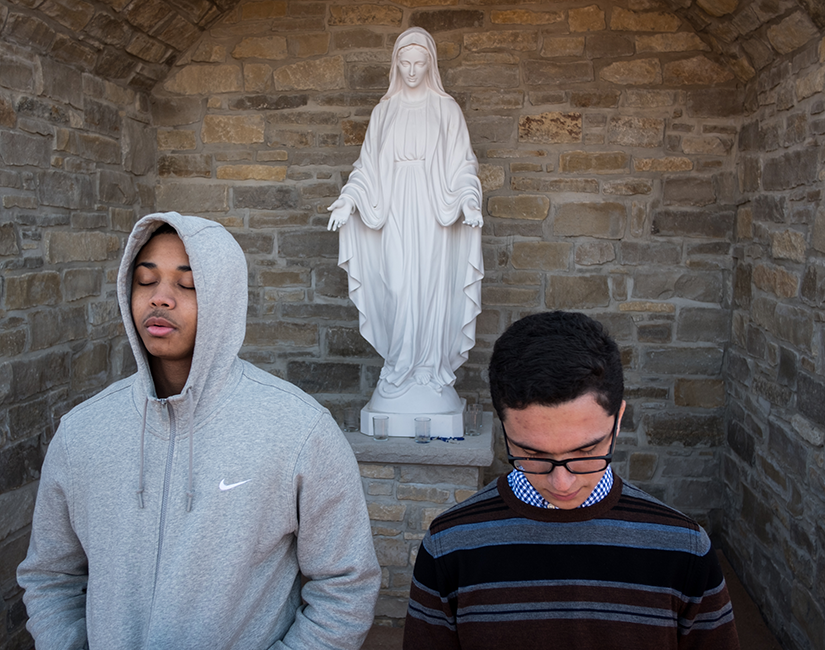

The decision to hold a prayer service for peace in the wake of another school shooting was an easy one for students at Christian Brothers College High School in Town and Country.

Determining the place to have the service was even easier — the Blessed Mother Grotto, in front of Our Lady of Peace.

The reflective service was organized by students and led by the school’s campus minister, Dominican Father DePorres Durham, who stated in the introduction that it was intended to recognize the pain and anxiety and “give voice to our suffering after the senseless act of another school shooting.”

The students and staff members who attended the prayer service, many wearing hoodies on a chilly but sunny morning, circled around the grotto on a high point of the campus overlooking the football stadium. They listened as the names of 27 schools impacted by shootings were read aloud and then were silent for 100 seconds at Father Durham’s suggestion to recommit to being “Men for Tomorrow, Brothers for Life.” After a half-dozen reflections, they prayed the Our Father and received a final blessing.

The presenters urged students to write a commitment to action and place it in a basket in the chapel. The suggestions included reaching out to someone at CBC who may be experiencing difficulties or is picked on, expressing love and care to a family member and more.

Danny White, a senior at CBC, said the prayer service was intended to show unity. “This was not about political action,” he said. “This was about standing in solidarity. As a Catholic school, we stand in solidarity through prayer and offering guidance from God.”

Through tough times, he said, “finding that light from God can help guide those who do not know the way.”

Father Durham said the grotto was selected because it is “a prayer place” and a site that is a long CBC tradition. Prayer is powerful, but action also helps overcome feelings of helplessness, he said. “While this is obviously a very complex problem, one way we can begin is to simply treat each other better,” the campus minister said. “It begins with recognizing the dignity of everybody we live with and that we are responsible for each other.”

Walk-out

For about an hour on March 14, Cardinal Ritter College Preparatory High School took to the streets of Midtown in support students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla.

Wearing orange arm bands or orange shirts, students, faculty and staffed marched about three-quarters of a mile to the corner of Grand Boulevard and Laclede Avenue at St. Louis University. Most carried posters they created for the occasion, with messages such as “#StopTheViolence,” “Enough is enough,” and “Blessed are the children.”

They lined up briefly along Grand, waved their signs and cheered as passing motorists honked their horns in approval, before heading back to school.

The march had many poignant moments. Some students created posters memorializing the victims in Florida as well as victims of gun violence in St. Louis. Freshman Malachi Davis made a poster with a photo of 17-year-old Nicholas Dworet from Parkland, Fla., accompanied by snippets of Nicholas’ plan after high school to pursue competitive swimming this fall in college.

The poster project drove home the harsh reality that Dworet “was really dead,” Davis said, adding that creating the poster “was hard; he didn’t deserve to lose his life. … I’m sure he didn’t wake up in morning thinking, ‘I’m going to die today.’”

He likewise couldn’t imagine the shooter “waking up thinking that he’s going to shoot another person and take their life. … It’s really sad. It makes me really think about life.”

Some in the Cardinal Ritter community have lost loved ones or friends to gun violence in the St. Louis area, including Ronnie Robinson — the father of 2013 Cardinal Ritter graduate Breonna Robinson. Two of his sons have died as a result of gun violence in the past three years: Lonnie, as an innocent bystander of a nightclub shooting in Illinois; Breyon, whose body was burned and thrown into a dumpster; he had been shot nine times.

Robinson described the march as “a show of unity; a lot of people don’t have unity anymore,” he said, though he feels the unity of the Cardinal Ritter community, which has supported him through the loss of his sons.

“I’m just honored they invited me back,” said Robinson, who volunteered at Cardinal Ritter during his daughter’s years there and beyond.

On the front lines

The mental-health debate falls under the purview of Catholic Family Services, a federated agency of Catholic Charities of St. Louis. With counselors embedded in more than 120 area schools, about 70 percent of them Catholic, the counseling service is on the front lines of the mental-health issue.

Catholic Family Services counselors give students, faculty, administrators and staff the tools to help mitigate mental-health concerns, thereby preventing circumstances that might lead to such tragic events.

“If we’re teaching the whole child, maybe some of these events don’t escalate,” said Tom Duff, the executive director of Catholic Family Services. “Is suspending (students) the right thing to do, or is it better to work with them and help the solve the problem?”

The agency certainly prefers the latter over the former.

“Our school partnership program is all about that emotional regulation,” Duff said. “A lot of times, when kids are struggling, it might not even be a true mental-health issue. Maybe it’s an emotional-regulation issue; maybe they’re being traumatized and they don’t have the skills to work through that.”

Embedded counselors serve at schools for as little as a half-day per week to five days a week, depending on schools’ needs. Through Trauma 101 training, they also help educators identify at-risk students in need of assistance, and they give students an on-staff advocate to avoid embarrassment of perceived weakness or inadequacy in seeking assistance to address toxic stress related to situations at home or in the neighborhood.

Adding mental-health education to general health education also might pay big dividends.

“What would happen if we put a big emphasis of mental health?” Duff asked. “What happens if we have a whole semester on mental health instead of one day on mental health in health class. What happens if students start understanding each other better?”

By learning to understand each other, with the help of counselors, educators and each other, students will learn that “it’s OK to be different,” Duff said.

Catholic Family Services

By the numbers

8 • Offices throughout the area

75 • Counselors, including 45 embedded in school settings

120 • Area schools (parochial, private and public) with embedded therapists

2,500 • Professionals, including counselors and teachers, trained in trauma-informed care

4,216 • People served per year through the eight offices

11,000 • Dollars per year to embed one therapist in a school for one day a week

12,000 • Students in schools with embedded therapists

School shootings have prompted debates about gun control and conversations about mental health, but the recent shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., has added another voice … United against violence

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.