God is Calling

St. Louis needs to be an example for racial equity and human dignity

After the death of Michael Brown in 2014, shot in a confrontation with a police officer, Josh Meister had an awakening.

“The situation opened my eyes to the fact that there’s still a lot of racial tension and I didn’t really realize it,” Meister said.

Fast forward three years to the not guilty verdict of former St. Louis Police Officer Jason Stockley — a white officer charged with first-degree murder in the shooting death in 2011 of Anthony Lamar Smith, a known drug dealer who was black. Meister realized it was time to put his faith into action.

One of Meister’s first stops was the archdiocese’s social justice conference Sept. 30 at the Cardinal Rigali Center. Meister, a psychology student at Webster University, had heard about the conference through Washington University’s Catholic Student Center, where he attends. With an interest in the mental health profession, Meister attended a session Sept. 30 that covered mental health care and the future of Medicaid funding.

He was one of several people new to the social justice movement in attendance at the conference. The event was the first for the archdiocesan Peace and Justice Commission, which started planning it in the spring as a call to action, especially for those who were becoming more engaged since Ferguson. The conference, organized with the Office of Laity and Family Life, St. Charles Lwanga Center and Catholic Charities of St. Louis, covered topics including the death penalty, school to prison pipeline, immigration and poverty.

“We had everywhere from 15-year-olds to 80-year-olds register,” said Peace and Justice Comission director Marie Kenyon. “It was a broad range of people, and we wanted to have something for everyone.” The commission, formed by Archbishop Robert J. Carlson in 2015, has been at work identifying priorities for moving forward since Ferguson. The conference was just one concrete action.

Archbishop Carlson brought together a group of faith leaders last month for an interfaith prayer service after the Stockley verdict. There, he noted that seeking peace should not be an unrealistic dream. An affirmation of peace in the world is a public commitment to justice. “Where there is no justice, there cannot be peace,” said the archbishop. “Peace and justice are not in competition.”

Last week, the archbishop invited a group of ministers to meet with him to discuss racism, poverty and other related issues. “Together as a group of ministers, men and women, I want to begin a process of not only working toward justice, but also more necessary areas of reconciliation,” he told the Review. “We have to find ways that God would inspire us to be brothers and sisters to one another — or as the way I see it, to see our neighbors as ourselves.”

Besides the faith community, the archbishop said he wants to reach out to other groups, including the police and those who have been leading the protests. Part of that is a desire to foster communication and build relationships, but also to help impart an understanding that there are no sides in the movement toward peace and justice.

“We have to take a step back and lower the rhetoric,” he said. “We have to put on our civility and begin to actually listen to each other.”

Is St. Louis the new Selma?

Shortly after Michael Brown’s death, Archbishop Carlson announced he was re-establishing an archdiocesan commission on human rights. The Peace and Justice Commission, he said in a statement, will “assist the citizens and public officials throughout all 11 counties of our archdiocese in the effort to achieve peace and justice for all.” In particular, the commission was going to look at these issues through the lens of the family, which the Church teaches is the basic structure of humanity.

The archdiocese was uniquely positioned to take on the task with its long history of providing education in Catholic schools, social services through Catholic Charities of St. Louis and its eight affiliate agencies, and health care service in Catholic hospitals. Many parishes, especially those on the north side of the archdiocese, also have long been active in addressing some of the issues.

Now more than two years into its work, the commission’s Racial Equity Committee has been planning ways to address the issue of racial equity in the archdiocese, from the top down. In a draft report, the committee is looking at ways to improve within the areas of education, employment and engagement of the faith community. Specific examples include piloting a workshop on racial equity for Catholic school staff, working with the archdiocese’s Human Resources department to achieve better diversity in the workforce, doing more business with minority-owned vendors and exploring more opportunities for parishes to collaborate with one another through a cultural exchange program.

“We have a lot of work to do here in our pews and our schools,” Kenyon said. “I sometimes hear people complain, ‘Why is the Church involved and becoming political?’ Part of it is recognizing the systems that are biased. I was a lawyer for 27 years and saw every day the systemic racism in the legal system. We have an obligation to realize that racism is rampant in our community and if we don’t do something to eradicate it, we can’t complain about the unrest and turmoil.”

In his keynote at the social justice conference, Rev. Starsky Wilson, former co-chair of the Ferguson Commission, called on St. Louis to write a new chapter in the city’s “unfinished business.” Calling on the faith community, he said, “you are not fishers of men. You are fishers of humanity.”

The archdiocese is in a position to continue the work of racial equity, much in the fashion of the women religious like Sister Antona Ebo and Sister Barbara Moore, who marched for civil rights in Selma, Ala., in 1965. With the recent events in St. Louis, some, including Kenyon, are calling this city the “new Selma.”

“God has given us so many signs,” she said. “We’ve had two major events in three years. This is a sign to us that things aren’t right and He’s saying, ‘I’m expecting you to fix it.’ The region and the country are looking at us.”

Social justice + pro-life

The Church has long held that there is no distinction between defending human life and promoting the dignity of the human person. Pope Benedict XVI, in “Caritas in Veritate,” noted that “the Church forcefully maintains this link between life ethics and social ethics, fully aware that a society lacks solid foundations when, on the one hand, it asserts values such as the dignity of the person, justice and peace, but then, on the other hand, radically acts to the contrary by allowing or tolerating a variety of ways in which human life is devalued and violated, especially where it is weak or marginalized.” (“Caritas in Veritate,” no. 15).

Quite simply, social justice is a matter of being pro-life. And vice-versa.

Racism, said Kenyon, is a “pro-life issue, because it’s all about the dignity of the human person. I don’t see how you can look at racism and not see it’s fundamentally a pro-life issue.”

Kenyon said she’d like to see the efforts of the Peace and Justice Commission and the archdiocesan Respect Life Apostolate come together in a more concentrated way. “This would send the message that this is all one big issue,” she said.

Theater performance highlights racial differences growing up Catholic in St. Louis

Rock, College churches to host performance Oct. 14 and 15 at SLU

BY JENNIFER BRINKER | jbrinker@archstl.org | twitter: @jenniferbrinker

Growing up Catholic in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s surely will elicit many memories from people of that generation — transitioning from Mass in Latin to the vernacular after the Second Vatican Council, being taught mostly by nuns and the desegregation of Catholic schools.

What were those experiences like growing up black and Catholic? How did they differ from being white and Catholic?

Those questions will be addressed in a production of “Growing Up Catholic: What’s Race Got to Do With It?” later this month at Tegeler Hall at St. Louis University. The performance is the collaborative effort of members of St. Alphonsus “Rock” and St. Francis Xavier “College” churches.

Members of the two parishes formed a relationship three years ago after the events in Ferguson. Their purpose was to develop a relationship among members of two parishes — the Rock Church is predominantly African-American, and College Church has a large Caucasian membership.

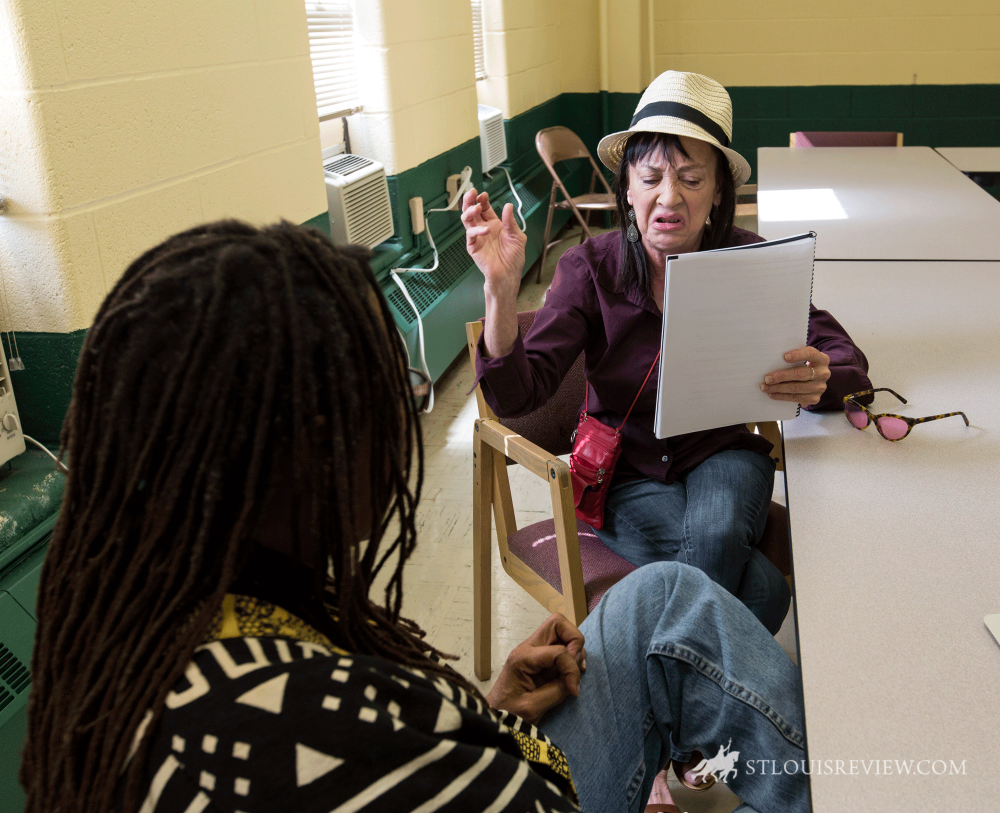

The play, which debuted last year at Fontbonne University, shares the real-life memories of eight women now in their 60s who grew up Catholic in St. Louis, said Thomasina Clarke, a professional actress and playwright, who helped write the script.

“We are bringing to the forefront what it was like being black, being white, being Catholic in St. Louis,” said Clarke, an African-American woman who was taught by the Daughters of Charity at Laboure High School in the 1970s.

Clarke recalled in high school when she and a group of black students asked if they could put on a black history program. She chuckled, pointing out the absurdity of how they were given only 15 minutes to make their presentation to the school.

Racism, unfortunately, still exists, even within the Church, Clarke said. “The play is factual — there’s nothing in here that we made up. These incidents took place and it is to open the minds of the audience.”

In addition to the personal stories, the performance will highlight the history of numerous black saints and other historical figures, including Moses the Black, several African popes and Sts. Perpetua and Felicity.

Rock parishioner Almetta “Cookie” Jordan connected with several people in the theater community, including Thomasina Clarke and LaVelle Wilkins-Chinn, who also helped write the script.

“We thought, why don’t we do a theater piece?” Jordan said. “Through the arts we can tell people about something. We can have a panel (discussion), but theater really motivates people and makes people think.”

The play is dedicated to Agnes Wilcox, who was in the original production in 2016 and Tony McDonald, a College Church parishioner who helped inspire the collaboration. Both died in the past year.

Ultimately, by bringing these stories forward and seeing the differences, hopefully people will hear the importance of loving one another, Clarke said. “It’s inherent that we love and want to be loved,” she said. “And for those who don’t have that, it’s difficult.”

Take Action

Forward Through Ferguson: After the death of Michael Brown in 2014, a group of regional leaders, The Ferguson Commission, studied racial inequities and developed a path toward change. To learn more or to read the commission’s report, visit www.forwardthroughferguson.org.

For the Sake of All: The project began in March 2013 as a collaboration between scholars at Washington University and St. Louis University to report on the health and well-being of African Americans in the St. Louis region by highlighting social, economic and environmental factors that drive differences in outcomes. The site, www.forthesakeofall.org, includes specific action items.

Archdiocesan Peace and Justice Commission: Founded in 2015 by Archbisop Robert J. Carlson, the commission has developed priorities looking at how issues affecting the region specifically impact the family. To learn more, visit www.archstl.org/peace-justice.

St. Charles Lwanga Center: The archdiocesan office of black Catholic ministries provides spiritual formation and leadership, including advocacy for justice and racial equity concerns, within the African-American Catholic tradition. See www.archstl.org/lwangacenter

Living Justice Ministry at St. Margaret of Scotland: The parish-based ministry has numerous activities, including dialogue events and calls to action. The group is LivingJusticeSMOS on Facebook. Or email LivingJusticeSMOS@gmail.com.

Social Justice 4 All: A group of volunteers in north St. Louis and west St. Louis County who are inspired by the Holy Spirit to improve lives for all in St. Louis. For information, contact Bernie Sammons at berniesammons@aol.com

SPARC (Students Participating Actively in Real Change): A student-led group that meets monthly to plan events for social justice/diversity clubs in St. Louis schools, and serves as a network for students interested in these issues. To learn more, email stlsparc@gmail.com

Missourians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty: The nonprofit organization is dedicated to ending the use of the death penalty in Missouri. See www.madpmo.org.

Missouri Catholic Conference: The public policy arm of Missouri’s bishops serves as an advocate for different issues in the Missouri legislature. See www.mocatholic.org.

After the death of Michael Brown in 2014, shot in a confrontation with a police officer, Josh Meister had an awakening. “The situation opened my eyes to the fact that … God is Calling

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.