A long history of missionary work

Father De Smet, St. Rose Philippine Duchesne, others show the Church has history of ministering to Native Americans

The Mississippi River valley, with its tributaries feeding fertile prairies and woodlands, had long been populated by indigenous peoples. From the Mound Builders to the Illinois and Kaskaskia nations, generations of Native Americans hunted, trapped and farmed from their villages up and down the river valleys.

European settlers brought more than just their goods and livelihoods: they brought their faith. As early as 1673, Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette travelled by canoe into the Mississippi River valley spreading the Good News. The hope of these early missionaries was to convert native peoples to the Catholic faith while maintaining respect for their traditions and way of life.

Upon his arrival in St. Louis in 1818, Bishop Louis William Valentine DuBourg hoped to fulfill his missionary zeal by ministering to Native Americans. In 1820 he got his chance: a group of Osage chiefs came to ask Bishop DuBourg, the “chief of the blackrobes,” for priests to minister to them. Initially hoping to lead a missionary expedition, Bishop DuBourg instead sent Rev. Charles de la Croix, a priest from the St. Mary’s of the Barrens Seminary.

Bishop DuBourg procured a grant in 1823 from President James Monroe to support four missionary priests at three mission posts: Council Bluffs, the Minnesota River and Prairie du Chien. In addition, he and

Rev. Charles Nerinckx recruited a hardy group of Jesuits to work among the Indians.

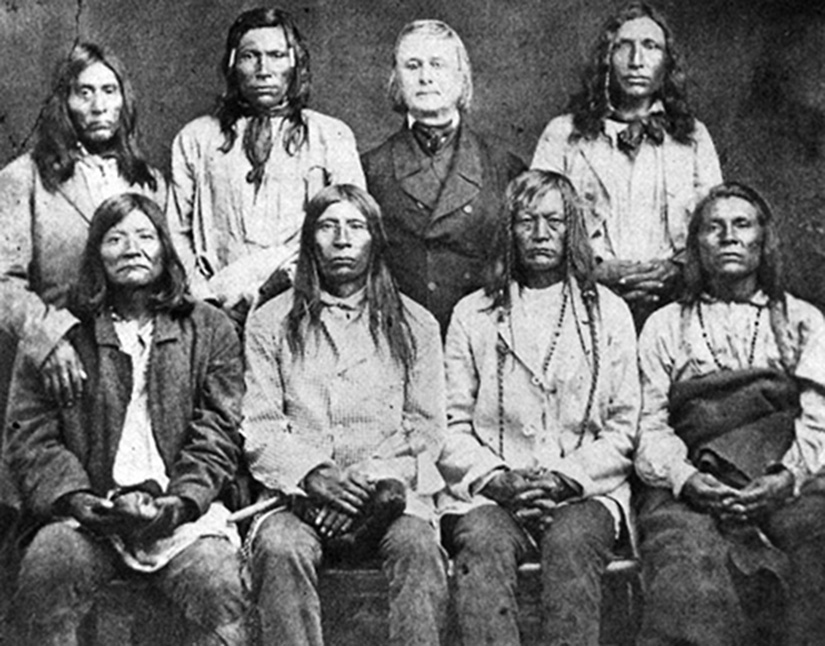

On May 31, 1823, Pierre Jean De Smet, a Belgian Jesuit novitiate, landed on the St. Louis riverfront. He would finish his studies and be ordained a priest at the Jesuit seminary in Florissant in 1827. Here he supplemented his knowledge of French with English and Native American languages and customs. In 1837, a delegation of Bitterroot Salish Native Americans arrived in St. Louis seeking missionary priests for their nation. Father De Smet petitioned Bishop Joseph Rosati to return with them, which was enthusiastically granted. Eventually Father De Smet would log more than 10,000 miles in his missionary work, travelling as far as the Oregon Territory to spread the Gospel and advocate for missions to Native Americans.

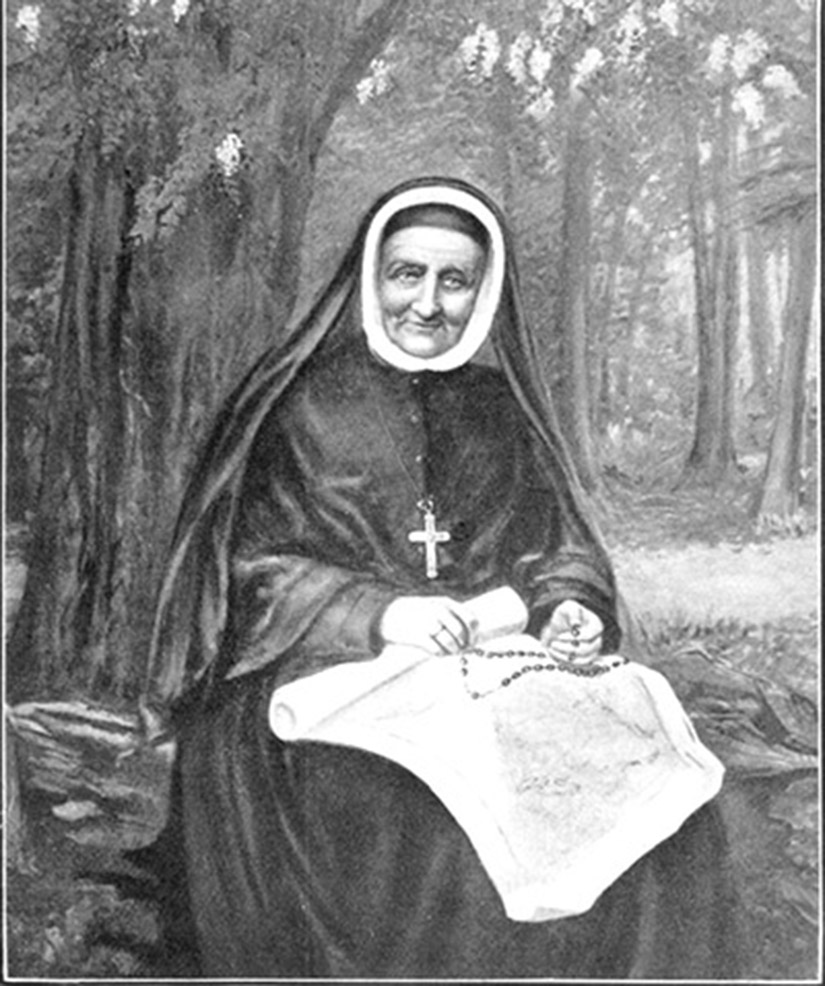

When St. Rose Philippine Duchesne left France for the New World, she felt a calling to missionary work. Upon her arrival, however, she immediately fulfilled a need by establishing schools in the new diocese. In 1841, she was given her chance at her original calling. A delegation left for the Potowatami mission at Sugar Creek, Kansas. Father Peter Verhaegen, upon learning she wished to go, declared, “Duchesne must come, too. Even if she can use only one leg, she will come. Why, if we have to carry her all the way on our shoulders, she is coming with us. She may not be able to do much work, but she will assure success to the mission by praying for us.” Upon arriving at the mission, St. Rose Philippine Duchesne wrote St. Madeleine Sophie Barat, her mother superior, stating, “My dearly loved Mother, at last we have reached the country of our desires.”

Unfamiliar with the language, she was unable to teach classes, so she spent most of her time in prayer, so much so that she became known as “Woman Who Prays Always.” Due to poor health, St. Rose Philippine was forced to bid the Potowatami farewell after a year and return to St. Charles in 1842.

Fair is the director of archives for the Archdiocese of St. Louis.

Father Pierre Jean De Smet with some of the Bitterroot Salish tribe.Photo Credits: Courtesy Archdiocesan Archives The Mississippi River valley, with its tributaries feeding fertile prairies and woodlands, had long … A long history of missionary work

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.