New film follows Father Gerald Kleba on tour through Black St. Louis history

The documentary will be part of the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase on July 27

When Father Gerald Kleba was pastor of the former St. Bridget of Erin Parish in north St. Louis, he celebrated a Mass in June to honor all the graduates in the parish.

A woman asked him if that would include the children who graduated kindergarten.

“I thought, ‘Oh, come on, everyone graduates kindergarten,’” Father Kleba said. “And she said, ‘Do you know how much my ancestors, our ancestors, suffered and got tarred and feathered because they learned how to read?’”

Father Kleba’s interest in Black St. Louis history stems from these years of experience in predominately Black neighborhoods in north St. Louis. He spent 10 years at Visitation Parish, then another nearly 10 at St. Bridget of Erin, in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s.

“It was in those times that I made great friends and got very involved with social justice,” Father Kleba said.

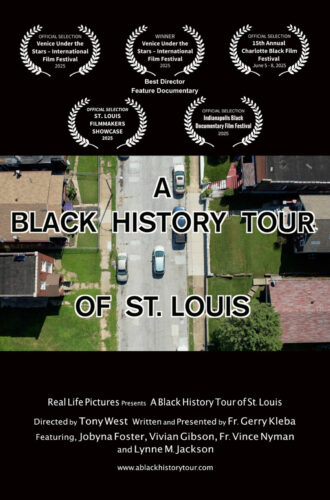

Now, his deep knowledge of that history is chronicled in a new film, “A Black History Tour of St. Louis,” directed by St. Louis native and videographer Tony West.

The 85-minute documentary follows Father Kleba as he gives a tour of important religious and secular places in Black St. Louis history. It debuted at the Venice Under the Stars International Film Festival earlier this year, netting a win for best director — feature documentary, and was also part of the Charlotte Black Film Festival. The film will be featured in the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase on July 27 at the Hi-Pointe Theatre in St. Louis.

The first Black history tour Father Kleba offered was to Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski, shortly after he arrived in the Archdiocese of St. Louis. Archbishop Rozanski mentioned the tour at the first Mass of Racial Unity in 2022, and several in attendance asked Father Kleba when they could go on the tour.

From 2022 to 2025, Father Kleba led 20 tours for approximately 400 people, he said.

The film follows his typical tour route, which includes historic locations of the 1800s, like the Old Courthouse and the Old Cathedral, as well as those that Father Kleba had a hand in. Father Kleba helped found and served as the first president of the St. Louis Association of Community Organizers (SLACO), and also founded the former Visitation Community Credit Union, which gave small loans to people in the neighborhood.

His knowledge of Black history came directly from his experience living in the community and forming relationships with the people, he said.

“Just try to make loans to people in north St. Louis to find out all about the economic history of racism,” he said. “If you want to know something about history, listen to people talk to you at the luncheon after their grandma’s funeral.”

Visitation Parish, where he served from 1973-83, is “a key place for racial justice in St. Louis, because a pastor named John Hamilton Smith integrated the school there 10 years before Brown v. Board of Education,” he said. “…Then, Archbishop (Joseph) Ritter, when he came here, was pretty quick to integrate the schools and parishes in the archdiocese.”

The film also includes interviews with Jobyna Foster, a graduate of Homer G. Phillips Nursing School; Lynne Jackson, a descendent of Dred and Harriet Scott; Vivian Gibson, author of “The Last Children of Mill Creek;” and Father Vince Nyman, a longtime pastor of the former Our Lady of the Holy Cross Parish in Baden.

The arrival of the film coincidentally coincides with the end of his bus tours, Father Kleba said. The May 16 EF-3 tornado caused heavy damage to many of the buildings and locations along the route.

“I’m brokenhearted about the storm damage,” he said. “But on the flip side, I’m elated because the movie’s here — you want to know what Centennial Christian Church looked like? It’s in our movie. You want to see Fountain Park with trees and the statue of Dr. Martin Luther King standing on the pedestal proudly? It’s in our movie.”

Director Tony West met Father Kleba when he interviewed the priest for his first documentary, “The Safe Side of the Fence,” which explores the legacy of nuclear projects in the St. Louis area.

Father Kleba invited him to come on a Black history tour and film it; West agreed, thinking it would just be a nice recording to be able to give to his priest friend. Since he didn’t want to distract from the tour by bringing his camera equipment onto a crowded bus, Father Kleba gave him a private tour by car.

“I wasn’t halfway into that tour when I was just amazed by what I was learning from him. I’m figuring, I’m African-American, I’ve been living in St. Louis my whole life, and I work in television, so I figured I would know most of the stuff he was talking about,” West said. “But I didn’t know a lot. And I think what makes it fascinating for me is that he knows the history of the Catholic Church and he also knows the history of Black churches in the community, because he’d been there for decades; those histories are entwined, and he’s able to speak on both of them.”

After recording the first tour, West retraced their route, filming the locations along the way. Then, over the next year — with Father Kleba’s help — he tracked down the rest of the interviews that round out the film.

Father Kleba’s tour shows “how discrimination affects every aspect of your life, from getting a loan to the school you’re going to, your education, to arts — like Scott Joplin — to your medical care, the hospitals,” West said.

West’s mother grew up in the Carondelet neighborhood and was an adolescent when St. Louis schools were integrated. His aunt spent the first three years of high school being bused to Vashon High School but then became one of the first Black graduates of Cleveland High School.

The film is not a narrative of Black vs. white, he said. “There’s people who don’t believe in equality, versus people who do believe in it,” he said. “And you can be a person who does believe in it from any race.”

For Father Kleba, it was important to show not just the discrimination that has permeated Black history but also the hope that is present, too. “You see brokenness and you see deterioration, you see desertion, and it’s all really disheartening,” he said. “Also on this tour, you see countless community gardens, and you’re going to see housing developments in surprising places.”

It wasn’t just one person who created the racist policies that affected north St. Louis neighborhoods for generations to come, and it’s not just one person fighting for better polices and reinvestment. “It’s community organizations,” Father Kleba said. “Now the question you have to ask yourself is, which side are you on? Are you on the side of deterioration and desertion, or are you on the side of beauty and health and livelihood divine? That’s what we come here to learn on this trip.”

“We all have to know that we’re children of God, and that’s the most fundamental notion of the great commandment of love,” he said. “If we’re going to love our neighbor as ourselves…it’s because they are us and we are them.”

See the film

“A Black History Tour of St. Louis” will be shown at 3 p.m. Sunday, July 27, at the Hi-Pointe Theatre in St. Louis as part of the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase. For tickets, visit stlreview.com/blackhistorytour.

To watch the trailer, visit ablackhistorytour.com.

The documentary will be part of the St. Louis Filmmakers Showcase on July 27

Subscribe to Read All St. Louis Review Stories

All readers receive 5 stories to read free per month. After that, readers will need to be logged in.

If you are currently receive the St. Louis Review at your home or office, please send your name and address (and subscriber id if you know it) to subscriptions@stlouisreview.com to get your login information.

If you are not currently a subscriber to the St. Louis Review, please contact subscriptions@stlouisreview.com for information on how to subscribe.